📁 [archived] Project-oriented workflow

Be honest with yourself, how many times have you wanted to restart an on-going project from scratch throwing away the current folder? Or how many times have you had to rename files and adjust folder structure to make your project simple and clear? Not to mention, all these thousands of versions of your scripts that are dangling around in your mail box. Tired of this? Then, get on board and read my comments on how to make your project reproducible, portable, and self-contained.

Disclaimer: This post is outdated and was archived for back compatibility: please use with care! This post does not reflect the author’s current point of view and might deviate from the current best practices.

Introduction

We start by working up some intuition about these three key aspects rather than trying to grasp explicit technical definitions. In data science context, reproducibility means that the whole analysis can be recreated (or repeated) from scratch: executing scripts based on raw data must yield exactly the same results. It means, for instance, that if the analysis involves generating random numbers, then one has to set a seed (an initial state of a random generator) to obtain the same random split each time. Ideally, everyone should also have an access to data and software to replicate your analysis (it is not always the case, since data can be private), but this is already a domain of open science.

Portability means that regardless of the operating system or a computer, given a minimal prerequisites, the project should work. For instance, if the project uses a particular package that works only on Windows, then it is not portable. The project is also not considered portable, if it utilizes a particular computer settings, such as absolute paths instead of relative to your project folder (e.g., when reading the data or saving plots to files). Normally, you should be able to run the code on your collaborator’s machine without changing any lines in the scripts.

We call a project self-contained, when you have everything you need at hand (i.e., in the folder of your project) and your project does not affect anything it did not create. It is a bad idea to use a function that has been defined in the other of your projects. Not only anyone else who does not have the second project will suffer, but yourself, when your current project will be used on the other machine. Furthermore, if you need, for instance, to save processed data, then it should be saved separately, and not overwrite raw data. There is another term that has a similar meaning – isolated, which is related to dependencies of the project. This topic is extensively covered in the section on packrat dependency management system.

This post is an attempt to summarize the use of “sexy” tools and techniques to improve above-mentioned aspects of project significantly. Of course, one can immediately feel that these aspects are interrelated. As a consequence, techniques and practices we consider further improve several elements at a time, rather than focusing on a particular one. For instance, using consistent folder structure will make your project reproducible and portable, while properly managed dependencies will ensure that the project is self-contained and portable. That is why further content is organized by focusing on tools rather than on stand-alone aspects. But do not get fooled, it is not a yet another git / RStudio tutorial. There are dozens of tutorials, and I do not try to compete with them. Instead, I want to give an overview of useful things based entirely on my experience.

Now, you might ask yourself: why it is such a big deal? Well, first off, it gives more credibility to the research, because it can be verified and validated by a third party ( your peers). Furthermore, keeping the flow of analysis reproducible, portable and self-contained makes easier to proceed and to extend the project. At first glance, it might look like you spend more time organizing your project than doing actual analysis. However, in the long run you will save much more time that you can anticipate.

It’s like agreeing that we will all drive on the left or the right. A hallmark of civilization is following conventions that constrain your behavior a little, in the name of public safety. Jenny Bryan

Version control system

If you are reading this post I bet you have heard of (if not used) version control system. It allows to manage changes to files, especially of the source code history. Naming all advantages of VCS would be a hard task, and I only wish to emphasize the main ones. First off to begin with, VCS allows storing the versions of files properly. One can always revert to any previous version of any file of the project, not having tons of versions of the same file. If you keep your project on a hosting service, then it also backs up your most important files. Furthermore, distributed VCS makes it possible to collaborate in a straightforward way: your fellows have an access to the latest version of any files of the project at any time. Let’s face the truth, sending files via email or Dropbox is too messy. It is not dangerous even if you work on the same file at the same time, because VCS can merge the changes afterwards. Finally, branching deserves a separate mention, that is a possibility to deviate from the main flow of the analysis by having an independent stream, which can be merged back afterwards. Most common VCS are git, SVN (Subversion), Mercurial.

Remember I mentioned that your collaborators always have access to files? Well, it is only true if your machine is plugged into a network. Surely that might not always be the case. To cope with this issue hosting services are used, such as GitHub (works with git and SVN), GitLab (git), Bitbucket (git and Mercurial), SourceForge (git, SVN), etc. These guys host your repository (repo for short, a folder with all your project files) making it possible to share and publish. While most of the VCS are command line tools, hosting services provide a very convenient web-based interfaces in addition to their own sweet features.

Long time ago, when people mostly used Emacs and Eclipse as IDE for R, SourceForge in conjunction with SVN dominated. Nowadays, most of R projects are hosted on GitHub and use git. GitHub has many nice features, like Issues (that can be used for bug tracking, to-lists, etc), Pull requests, an integration with Slack messenger, etc. Also, GitHub is very easy to intgerate to RStudio.

There is quite a number of tutorials on this topic. I personally find Hadley’s chapter in R packages a very concise yet explicit cookbook. It covers main skills you might need, e.g. how to write good commits, etc.

Speaking about git, it is hard to avoid the topic of collaborating workflows. In a nutshell, there are three main workflows: centralized workflow, feature branch workflow, and forking workflow. Typically, a research project involves only a small number of collaborators who trust each other. If that’s the case, it makes sense to employ the centralized one, when everyone pushes into the central master branch. To deep dive into details of other workflows, please see the Bitbucket tutorial.

Last but not least, it is very important to master git commands and use them via shell. For simple commands one can still use built-in RStudio git interface. However, once you are ready to use extensively git, shell becomes essential.

Dependency management tool

It is very likely that your data science project depends on non-base R packages. R provides a very convenient way of installing packages via install.packages(), which by default stores all packages in one global repository. In most cases it is more than enough. However, sometimes different projects may depend on different versions of packages. For instance, the first project uses a function that has been deprecated from the current version. At the same time, the second project utilizes a function that appears only in the recent version of the package. A good example of such package would be ggplot2, which evolves significantly over the time and many functions of which have been deprecated.

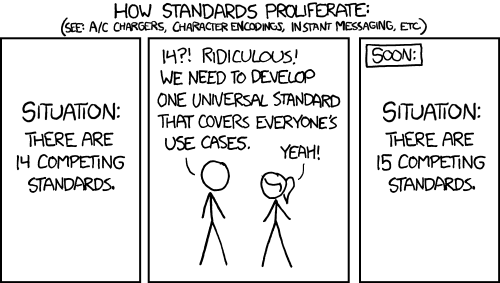

The solution to this problem is to store these packages of specific versions in the local folder of the project so that each project will have its own private package library. If you have previously used Python or Ruby, similar tools are virtual environments and bundle, respectively. In R we have several tools, such as packrat, jetpack, and others. The packrat is more common and stable, and below I briefly show how to use it.

Storing required packages in the folder of the project ensures the project is self-contained (meaning everything that the project needs is inside its folder), portable (you can move your project to another machine not worrying too much about dependencies), and reproducible (the same versions of packages yield the same result). In the official packrat web-page, the term self-consistent is replaced by isolated: indeed, this package manager not only makes sure that everything at hand, but also insures things won’t be overwritten and other projects won’t be affected (for instance, by installing a newer version of the dependence).

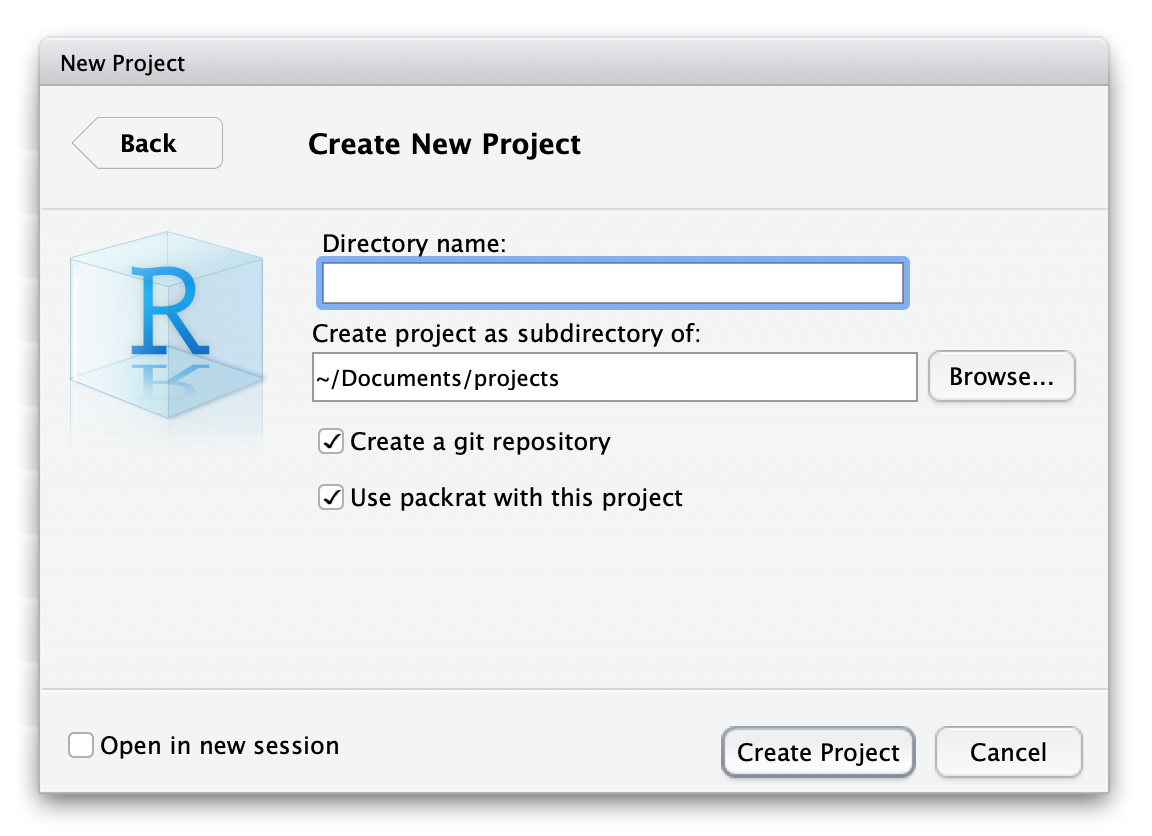

Installation of packrat is effortless, install.packages("packrat") should do the trick (on macOS it might require Command Line Tools to be installed first). To start using packrat you have two ways: if you use RStudio, then simply initialize a new project with packrat as shown below or use the command packrat::init() in the existing project (mind argument project, which by default is the working directory of R).

From now on all your packages will be stored in packrat folder. You should not modify anything by hand in this directory. I am not going to go over each component of this folder (one can read about it here), but several folders are worth mentioning. Files packrat/packrat.lock and packrat/packrat.opts contain the list of dependencies and specify the options of the tool, respectively. Then, packrat/lib/ is a repository, where your installed packages live, the actual private package library. Finally, your bundled packages are located in packrat/src/.

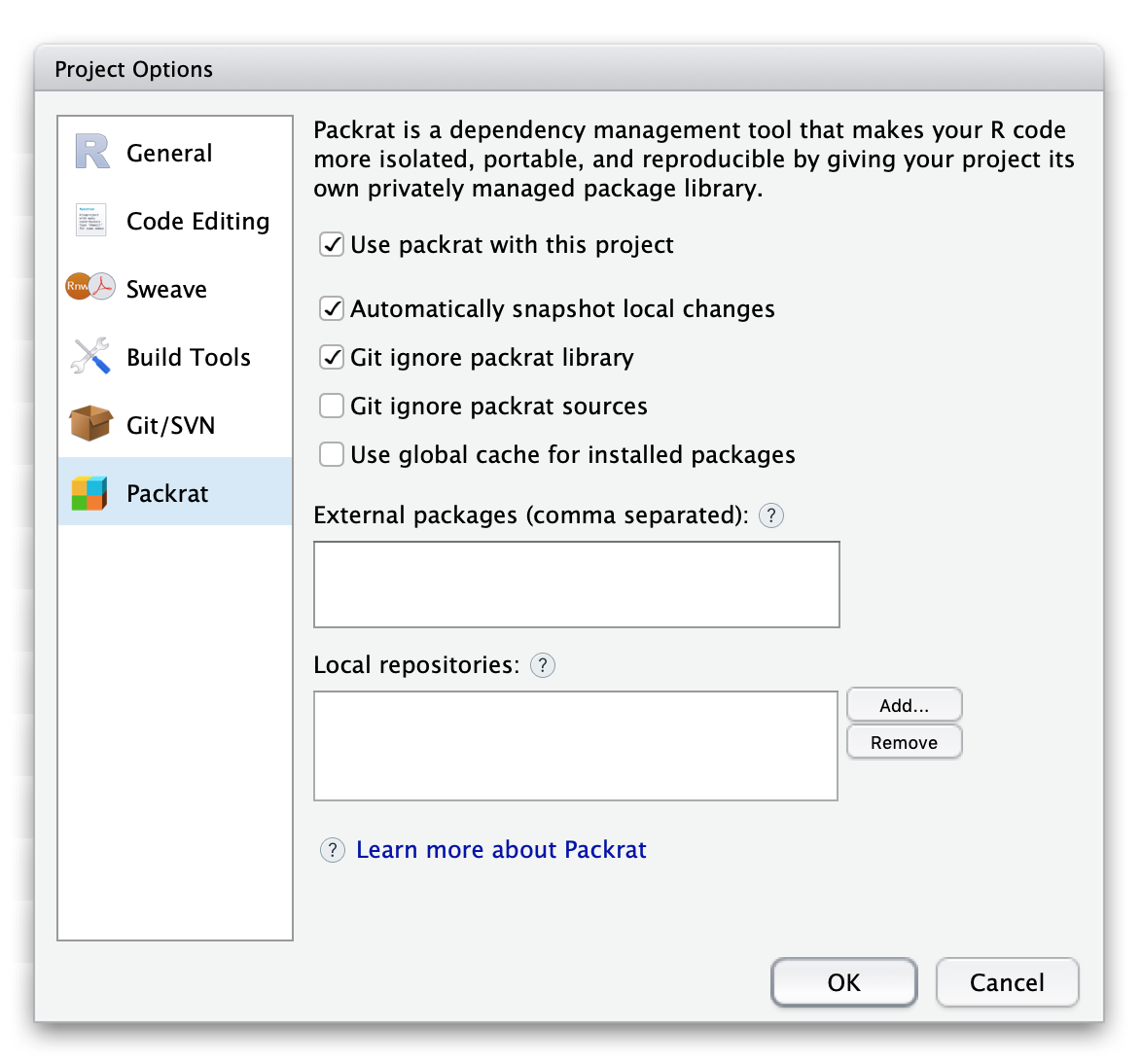

One has two ways to configure packrat: either with packrat::set_opts() or via RStudio (Tools -> Project Options… -> Packrat). Both methods will modify packrat/packrat.opts file. We add only one modification to default options: we need to check Automatically snapshot local changes in RStudio or to evoke packrat::set_opts(auto.snapshot = TRUE). We also leave Git ignore packrat library and Git ignore packrat sources as is, that is checked and unchecked. Installed packages in packrat/lib/ are platform-specific. Thus, carrying them to the other platforms does not make any sense. At the same time, they can be installed from bundled packages in packrat/src/, which will be transferred together with other files of the project.

The workflow of installing, removing, and updating packages is the same as in normal R, that is by install.packages(), etc. As long as we set auto.snapshot to TRUE, you do not need to make a snapshot each time by packrat::snapshot(), packrat will do it for you automatically.

The most amazing thing about packrat is if you move the project to the other computer, all you need to do is to start R from the project directory – packrat will set up the private package library automatically.

Project folder structure

The size of the project increases exponentially. A project started as a harmless code snippet can easily pile up into a huge snowball of hundreds files with an unstructured folder tree. To avoid this, it is important to define the folder structure before stepping into analysis. Depending on whether the project is a package or a case study, it should have a significantly different skeleton.

The folder structure of R packages is a subject to a regulation of community (CRAN and Bioconductor). It is well-defined and can be explored in R packages book, therefore, I skip it in this post.

As opposed to R packages, there is no a single right folder structure for analysis projects. Below, I present a simple yet extensible folder structure for data analysis project, based on several references that cover this issue.

The parent folder that will contain all project’s subfolders should have the same name as your project. Pick a good one. Spending an extra 5 minutes will save you from regrets in the future. The name should be short, concise, written in lower-case, and not containing any special symbols. One can apply similar strategies as for naming packages.

name_of_project/

|- data

| |- raw

| |- processed

|- figures

|- packrat

|- reports

|- results

|- scripts

| |- deprecated

|- .gitignore

|- name_of_project.Rproj

|- README.md

The folder data typically contains two subfolders, namely, raw and processed. The content of raw directory is data files of any kind, such as .csv, SAS, Excel, text and database files, etc. The content of this folder is read only, so that no scripts should change the original files or create new ones inside it. For this purpose processed directory is used: all processed, cleaned, and tidied datasets are saved here. It is a good practice to save files in R specific format, rather than in .csv, since the saving in .csv is a less efficient way of storing data (both in terms of space and time of reading/writing). The preference is given to .rds files over .RData (see why in Content of R files section). Again, files should have representative names (merged_calls.rds vs dataset_1.rds). Note that it should be possible to regenerate those datasets from the raw data. In other words, if you remove all files from this folder, it must be possible to restore all of them by executing your scripts that use only the data from raw directory.

The folder figures is the place where you may store plots, diagrams, and other figures. There is not much to say about it. Common extensions of such files are .eps, .png, .pdf, etc. Again, file names in this folder should be meaningful (the name img1.png does not represent anything).

All reports live in a directory with the corresponding name reports. These reports can be of any formats, such as LaTeX, Markdown, R Markdown, Jupyter Notebooks, etc. Currently, more and more people prefer rich documents with text and executable code to LaTeX and such.

Not all output object of the analysis are data files. For example, you have calibrated and fitted your deep learning network to the data, which took about an hour. Of course, it would be painful to retrain the model each time you run the script, and you want to save this model. Then, it is reasonable to save it in results with .rds extension.

Perhaps the most important folder is scripts. There you keep all your R scripts and codes. That is the exact place to use prefix numbers, if files should be run in a particular order. If you have files in other scripted languages (e.g., Python), it is better to keep them in this folder as well. There is also an important subfolder called deprecated. Whenever you want to remove one or the other script, it is a good idea to move it to deprecated at first iteration, and only then delete. The script you want to remove can contain functions or analysis used by other collaborators. Moving it firstly to deprecated ensures that the file is not used by other collaborators. It is not required, of course, because git keeps all versions, and it is always possible to revert. But from my experience, it is highly convenient.

There are three important files in the project folder: .gitignore, name_of_project.Rproj, and README.md. The file .gitignore lists files that won’t be added to Git system: LaTeX or C build artifacts, system files, very large files, or files generated for particular cases (e.g., packrat\lib). The name_of_project.Rproj contains options and meta-data of the project: encoding, the number of spaces used for indentation, whether or not to restore a workspace with launch, etc. The README.md briefly describes all high-level information about the project.

The proposed folder structure is far from being exhaustive. You might need to introduce other folders, such as paper (where .tex version of a paper lives), sources (a place for your compiled code, e.g., C++), references, presentations, NEWS.md, TODO.md, etc. At the same time, keeping empty folders could be misleading, and it is better to remove them (unless you are planning to store anything in them in the future). Moreover, git does not track empty folders.

Several R packages, namely ProjectTemplate, template, and template are dedicated to project structures. It is also possible to construct a project tree by forking manuscriptPackage or sample-r-project repos. Using a package or forking a repo allows automated structure generation, but at the same time introduces many redundant and unnecessary folders and files.

Finally, some scientists believe that all R projects should be in a shape of a package. Indeed, one can store data in \data, R scripts in \R, documentation in \man, and the paper in \vignette. The nice thing about it is that anyone familiar with an R package structure can immediately grasp where each type of file is located. On the other hand, the structure of R packages is tailored to serve its purpose – make a coherent tool for data scientists and not to produce a data product: there is no distinction between function definitions and applications, no proper place for reports, and finally there is no place for other script languages that you can use (e.g, Bash, Python, etc.).

Content of R files

While there are no rules on how to organize your R code, there are several dos and dont’s that most of the time are not taught explicitly. I list them below in no particular order:

-

Do not use the function

install.packages()inside your scripts. You are not supposed to (re)install packages each time you run your files. By default it is assumed that all packages that are used by a script are already installed. If you usepackrat, packages will be installed automatically from bundles.If there are many packages to install and you do not use

packrat, I suggest to create a fileconfigure.R, that will install all packages:pkgs <- c("ggplot2", "plyr") install.packages(pkgs)The snippet above profits from the fact that

install.packages()is a vectorized function. Anyway, most times,install.packages()is supposed to be called from the console, not the script. -

Do not use the function

require(), unless it is a conscious choice. In contrast tolibrary(),require()does not throw an error (only a warning) if the package is not installed. -

Use a character representation of the package name.

# Good library("ggplot2") # Bad library(ggplot2) -

Load only those packages that are actually used in the script. Load packages at the beginning of the script.

-

Do not use

rm(list = ls())that erase your global environment. First, it could accidentally delete accidentally an important long-time-to-build object. Second, it gives the illusion of the fresh start of R. -

Do not use

setwd("/Users/irudnyts/path/that/only/I/have"). It is very unlikely that someone except you will have the same path to the project. Instead, use a packagehereand relative paths. The packagehereautomatically recognizes the path to the project, and starts from there:# Good library("here") cars <- read.csv(file = here("data", "raw", "cars.csv")) # Bad setwd("/Users/irudnyts/path/that/only/I/have/data/raw") cars <- read.csv(file = "cars.csv") -

If your script involves random generation, then set a seed by

set.seed()function to get the same random split each time:# Good set.seed(1991) x <- rnorm(100) # Bad x <- rnorm(100) -

Do not repeat yourself (DRY). In R context it means the following: if the code is repeated more than two times, you had better wrapped it into a function (the example is borrowed from Advanced R):

# Better fix_missing <- function(x) { x[x == -99] <- NA x } df[] <- lapply(df, fix_missing) # Bad df$a[df$a == -99] <- NA df$b[df$b == -99] <- NA df$c[df$c == -98] <- NA df$d[df$d == -99] <- NA df$e[df$e == -99] <- NA df$f[df$g == -99] <- NA -

Separate function definitions from their applications. I typically keep a file

util.R, where all my functions are defined. -

Use

saveRDS()instead ofsave():

save()saves the objects and their names together in the same file;saveRDS()only saves the value of a single object (its name is dropped).load()loads the file saved bysave(), and creates the objects with the saved names silently (if you happen to have objects in your current environment with the same names, these objects will be overridden);readRDS()only loads the value, and you have to assign the value to a variable. Yihui Xie

initializing a new data analysis project in RStudio and getting your things together

Prerequisites:

- Installed and configured git

- Installed R and RStudio

- Existing account in GitHub

- Installed and configured

packrat

Steps:

-

Pick a good name (e.g.,

beer). -

In RStudio create a project:

- Navigate to File -> New project…

- Select New Directory

- Select New project

- Insert your picked name into Directory name

- Check Create a git repository and Use packrat with this project

This creates a folder with the name of the project, initializes a git repo, generates an

.Rprojfile, initializespackrat, and creates.gitignorefile. -

Configure

packratas described above. -

Populate folders with files. Typically, at the beginning, it is only

data/raw. -

Create a

README.mdfile. -

Launch

Terminaland navigate your working directory (ofTerminal, notR) to your project folder by, for instance,cd /Users/irudnyts/Documents/projects/beer. -

Record changes by

git add --alland commit bygit commit -m "Initialize the project". Traditionally the message of the first commit is simple"First commit", but I prefer to write something more conscious. Now all you changes are recorded locally. Note also that git does not record empty folders. -

Create a new repo in GitHub:

- Fill in

Repository namewith the same name as your project. - Fill in

Descriptionwith one line that briefly explains the intent of the project and ends with full stop. - Hit

Create repository.

- Fill in

-

Connect your local repo to your GitHub repo by

git remote add origin git@github.com:irudnyts/beer.git git push -u origin masterRefresh the page in your browser to ensure that changes appear at GitHub repo.

Outro & acknowledgement

About a year ago I came across a brilliant post by Jenny Bryan. I was amazed by how elegantly she formalized and summarized many simple tricks that make the life of a data scientist more pleasant. I was so inspired that I could not miss the opportunity to present these ideas in tutorials to students during the fall semester. The idea that I contributed to the process of making projects more conscious was very satisfactory, and based on these tutorials I start the series of posts.

Many ideas and concepts are based on the works of Hadley Wickham and Jenny Bryan. Many thanks!

References

- Happy Git and GitHub for the useR

- R packages

- Project-oriented workflow

- save() vs saveRDS()

- Jupyter And R Markdown: Notebooks With R

- A sample R project structure

- sample-r-project repo

- Creating an analysis as a package and vignette

- Analyses as Packages

- Packages vs ProjectTemplate

- Organizing the project directory

- Designing projects

- Project Management With RStudio

- Folder Structure for Data Analysis

- Organizing files for data analysis

- A meaningful file structure for R projects

- Packaging data analytical work reproducibly using R (and friends)

- What’s in a Name? The Concepts and Language of Replication and Reproducibility

- Packaging Your Reproducible Analysis

- Tools for Reproducible Research

- Data Analysis and Visualization in R for Ecologists

- Stop the working directory insanity

- manuscriptPackage

- cboettig/template

- Pakillo/template

- A minimal Project Tree in R -ProjectTemplate

- Writing a paper with RStudio

- Reproducibility vs. Replicability: A Brief History of a Confused Terminology

- Does R provides a dependency management tool?

- Comparing Workflows

- What They Forgot to Teach You About R

- Pictures are taken from R Memes For Statistical Fiends Facebook page and xkcd