📈 [archived] Simulating Poisson process (part 2)

In previous post we discussed two common methods of Poisson process simulation. The reason why this trivial problem was of my interest is the fact that this is simplification of a larger scale problem of a classical ruin process.

Disclaimer: This post is outdated and was archived for back compatibility: please use with care! This post does not reflect the author’s current point of view and might deviate from the current best practices.

Let me remind that I focus on an extenssion of Cramér–Lundberg model with positive jumps, that is:

\[X(t) = u + ct + \sum_{i = 1}^{N_1(t)}X_i - \sum_{j = 1}^{N_2(t)}Y_j,\]where:

- $u$: is an initial capital;

- $c$ is a premium rate;

- $N_1(t)$ and $N_2(t)$ are Poisson processes of capital injections and claims with rates $\lambda_1$ and $\lambda_2$, respectively;

- $X_i$ and $Y_j$ are i.i.d. random variables modeling sizes of capital injections and claims, respectively.

We simplify this model to a bare minimum, which reflects the behaviour of Poisson processes, that is we set $u = 0$, $c = 0$. Further, we assume deterministic unit jumps: $X_i = 1$ and $Y_j = 1$. As result we have the following model:

\[X(t) = N_1(t) - N_2(t).\]Nice thing about this model is that we know exact distribution of $X(t)$. It is called Skellam distribution, which is covered in skellam package. Therefore, we can compare Monte-Carlo simulated estimates to their exact equivaletns.

Method 1

For Gerber-Shui function we need to simulate a path until the ruin. It means that the time horizon is not known a priori. As consequence, the algorithm that first simulates the number of jumps for a given time is not applicable. Therefore, the only possibility to simulate a path until the ruin is to exploit the fact that interarrival times of jumps are exponentially distributed. In case of only negative jumps the algorithm is quite simple: in while loop we add jumps to a path until the process is ruined (or any other stopping conditions, e.g. maximum iterations acheived).

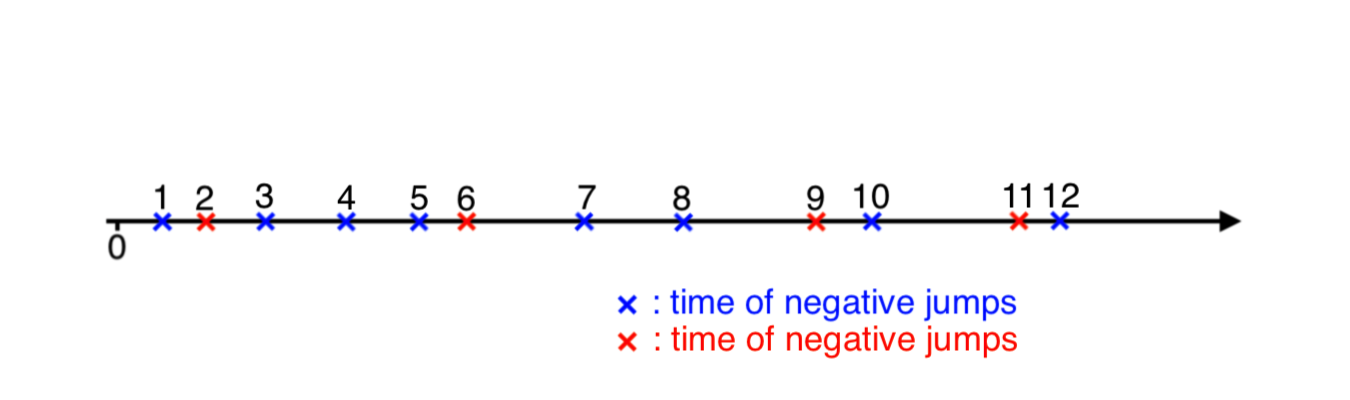

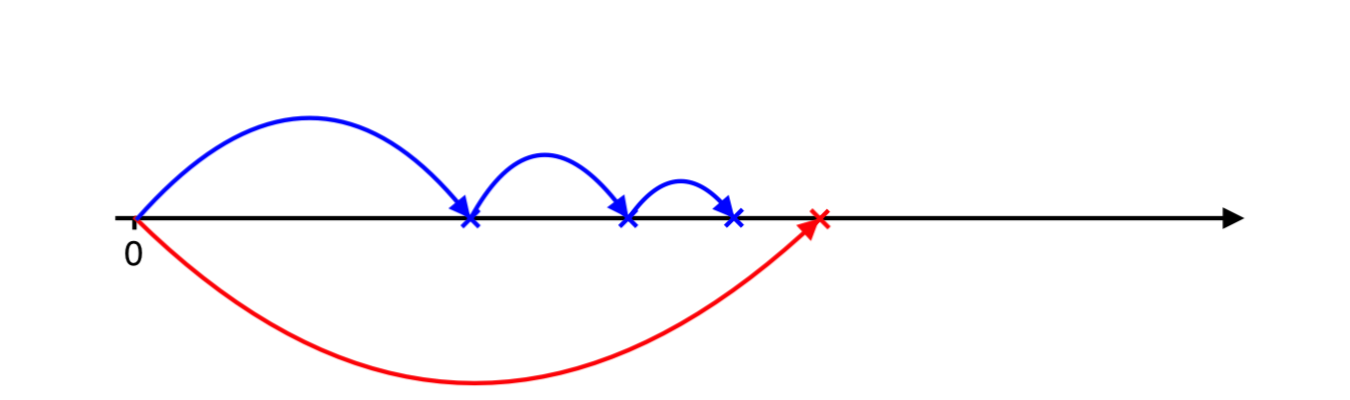

Things are slightly more complicated when the model includes positive jumps. If both positive and negative jumps’ times were known to us, then it would be possible to sort them, and add to a path in ascending order, as in an illustration below.

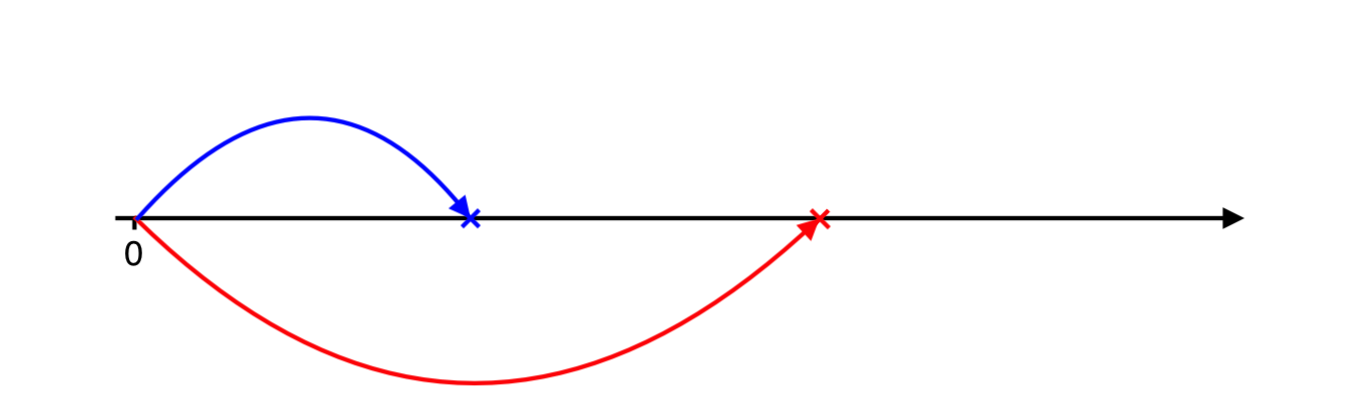

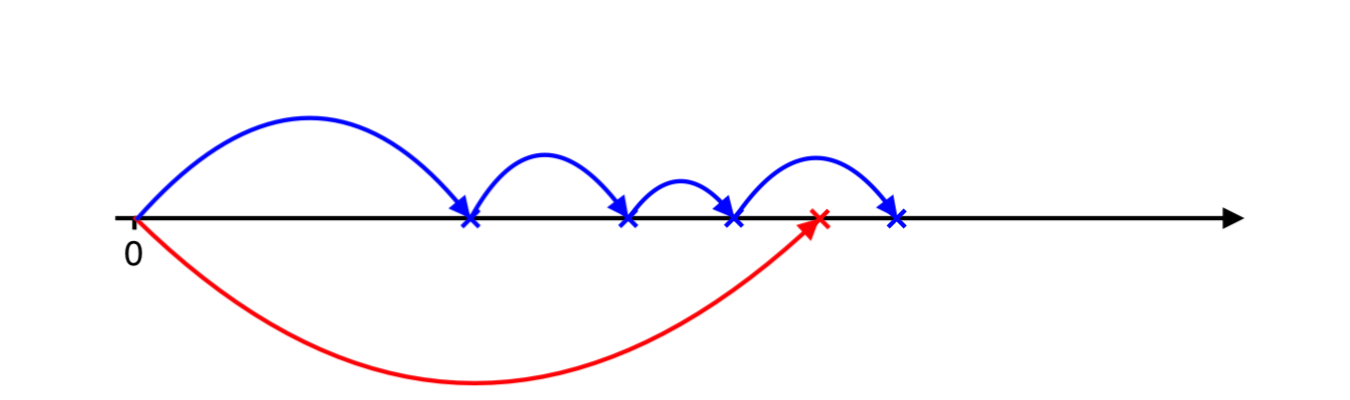

However, we do not know the arrival times of jumps, as they should be simulated. Also it would be naive to add a jump of one type at an iteration and then of another type in the next iteration, because underlying Possion process can have different rates (and, therefore, there is no garantee that one type jump follows the other type). The approach I propose here is very similar to a playground game “tag”. We generate arrival jump’s time for both types. Then, for one that occurred earlier (A), we need to catch up with the opposite type’s (B) time, that is generate more jumps of type (A) until the time of the later type (B) is achieved.

Algorithm:

- generate first times to negative and time to positive jump

- repeat

* if (time to last positive jump > time to last negative jump)

# add last negative jump to path

# if (stopping condition) exit loop

# repeat

% generate time to negative jump

% if (time to last positive jump < time to last negative jump)

@ exit loop

% add negative jump to path

% if (stopping condition) exit loop

# if (stopping condition) exit loop

* else

# add positive jump

# if (stopping condition) exit loop

# repeat

% generate time to positive jump

% if (time to last positive jump > time to last negative jump)

@ exit loop

% add positive jump to path

% if (stopping condition) exit loop

# if (stopping condition) exit loop

Let me illustrate a couple of iterations to give a feeling of the algorithm. We simulate positive and negative jumps’ arrival:

Positive jump occurs later, therefore, we need to catch up with negative jumps. We simulate next negative arrival…

And next negative arrival…

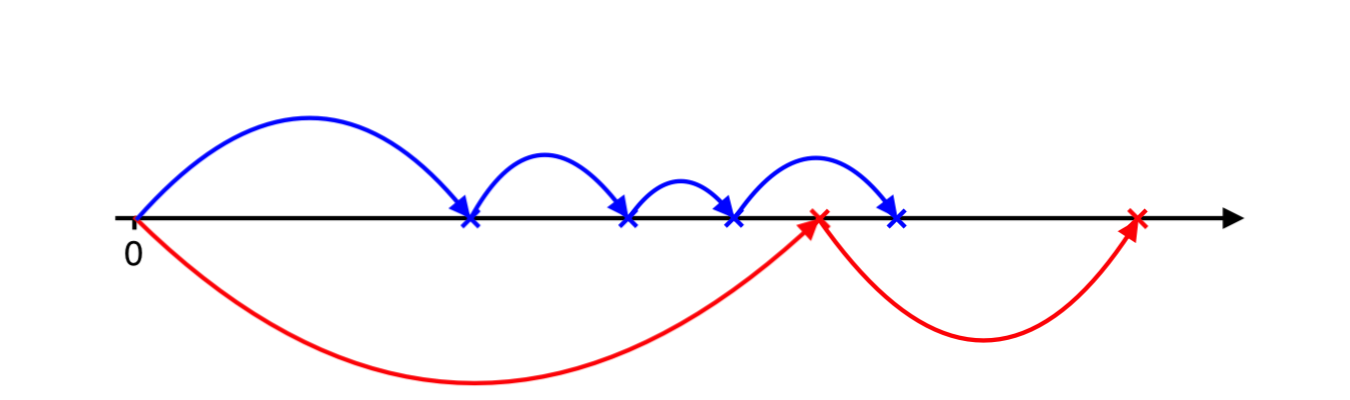

One more…

And finally the negative jumps over positive and now we need to catch up with positve ones…

And so forth and so on. In the algorithm above stopping condition could be anythin, for instance, a maximum number of jumps is attained, the maximum number of iterations is attained, the maximum time span is attained, the path is ruined, etc. Below, I propose an implementation with stopping time that uses a maximum time span.

library(magrittr)

library(ggplot2)

library(skellam)

sim_p1 <- function(lambda_p = 1, lambda_n = 1, t = 100) {

# utility function: get last element of a vector

last <- function(x) ifelse(length(x) > 0, yes = x[length(x)], no = 0)

# initialize process

path <- matrix(NA, nrow = 1, ncol = 2)

colnames(path) <- c("time", "X")

path[1, ] <- c(0, 0)

# function for adding negative jump to a path

add_jump_n <- function() {

# add a new time arrival to arrival times vector

time_n <<- c(time_n, current_time_n)

# add a negative jump to the path

path <<- rbind(

path,

c(current_time_n, path[nrow(path), 2])

)

path <<- rbind(

path,

c(path[nrow(path), 1], path[nrow(path), 2] - 1)

)

}

# function for adding positive jump to a path

add_jump_p <- function() {

# add a new time arrival to arrival times vector

time_p <<- c(time_p, current_time_p)

# add a positive jump to the path

path <<- rbind(

path,

c(current_time_p, path[nrow(path), 2])

)

path <<- rbind(

path,

c(path[nrow(path), 1], path[nrow(path), 2] + 1)

)

}

# check whether the path is reached maximum time span

is_max_time_span_attained <- function() path[nrow(path), 1] >= t

time_n <- numeric() # time of negative jumps arrivals

time_p <- numeric() # time of positive jumps arrivals

current_time_n <- rexp(1, lambda_n) # current time arrival of the negative

current_time_p <- rexp(1, lambda_p) # current time arrival of the positive

repeat{

if(current_time_p > current_time_n) {

add_jump_n()

if(is_max_time_span_attained()) break

repeat {

current_time_n <- last(time_n) + rexp(1, lambda_n)

if(current_time_p < current_time_n) break

add_jump_n()

if(is_max_time_span_attained()) break

}

if(is_max_time_span_attained()) break

} else {

add_jump_p()

if(is_max_time_span_attained()) break

repeat {

current_time_p <- last(time_p) + rexp(1, lambda_p)

if(current_time_p > current_time_n) break

add_jump_p()

if(is_max_time_span_attained()) break

}

if(is_max_time_span_attained()) break

}

}

# dropping last step to be before t

indices <- path[, 1] <= t

path <- path[indices, , drop = FALSE]

path <- rbind(path,

c(t, path[nrow(path), 2]))

rval <- list(

path = path,

time_p = time_p,

time_n = time_n

)

return(rval)

}

Let’s compare estimated expected value and variance of interarrival jumps with theoretical ones, for both positive and negative jumps. With default parameters $\lambda_1 = 1$ and $\lambda_2 = 1$, they all should be around one. This is confirmed in the code snipped below:

set.seed(2018)

p1 <- sim_p1(t = 1000)

mean(diff(p1$time_p)); var(diff(p1$time_p))

# [1] 0.9713893

# [1] 0.9399382

mean(diff(p1$time_n)); var(diff(p1$time_n))

# [1] 1.067944

# [1] 1.121641

Method 2

The second method is a bit less cumbersome. We simulate separately the number of positive and negative jumps in the interval $(0, t)$ by Poisson distribution with respective rates. Then, we generate arrival times of jumps by the uniform distribution, which is then sorted. Finally, the full path should be built, that is adding positive and negative jumps in a loop. The idea is as before: we compare what kind of jump (negative vs positive) occure earlier, and add the earliest one. Note, that it is possible that several negative jumps occure before a positive one, and vice versa. Also it is possible that only positive or only negative jumps are left, therefore, we need to incorporate this in the loop.

The implementation is presetned below:

sim_p2 <- function(lambda_p = 1, lambda_n = 1, t = 100) {

# simulate numbers of positive and negative jumps

number_p_jumps <- rpois(n = 1, lambda = lambda_p * t)

number_n_jumps <- rpois(n = 1, lambda = lambda_n * t)

# simulate the time of jumps' arrivals

p_jumps_arrival <- runif(n = number_p_jumps) %>% sort() %>% multiply_by(t)

n_jumps_arrival <- runif(n = number_n_jumps) %>% sort() %>% multiply_by(t)

# keep the time of jumps' arrivals in separate variables

time_p <- p_jumps_arrival

time_n <- n_jumps_arrival

# initialize process

path <- matrix(NA, nrow = 1, ncol = 2)

colnames(path) <- c("time", "X")

path[1, ] <- c(0, 0)

while(length(p_jumps_arrival) != 0 | length(n_jumps_arrival) != 0) {

if(length(p_jumps_arrival) != 0 & length(n_jumps_arrival) != 0) {

if(p_jumps_arrival[1] < n_jumps_arrival[1]) {

# add positive jump

path <- rbind(

path,

c(p_jumps_arrival[1], path[nrow(path), 2])

)

path <- rbind(

path,

c(path[nrow(path), 1], path[nrow(path), 2] + 1)

)

p_jumps_arrival <- p_jumps_arrival[-1]

} else {

# add negative jump

path <- rbind(

path,

c(n_jumps_arrival[1], path[nrow(path), 2])

)

path <- rbind(

path,

c(path[nrow(path), 1], path[nrow(path), 2] - 1)

)

n_jumps_arrival <- n_jumps_arrival[-1]

}

} else {

if(length(p_jumps_arrival) != 0) {

# add positive jump

path <- rbind(

path,

c(p_jumps_arrival[1], path[nrow(path), 2])

)

path <- rbind(

path,

c(path[nrow(path), 1], path[nrow(path), 2] + 1)

)

p_jumps_arrival <- p_jumps_arrival[-1]

}

if(length(n_jumps_arrival) != 0) {

# add negative jump

path <- rbind(

path,

c(n_jumps_arrival[1], path[nrow(path), 2])

)

path <- rbind(

path,

c(path[nrow(path), 1], path[nrow(path), 2] - 1)

)

n_jumps_arrival <- n_jumps_arrival[-1]

}

}

}

# add last step

path <- rbind(path,

c(t, path[nrow(path), 2]))

rval <- list(

path = path,

time_p = time_p,

time_n = time_n

)

return(rval)

}

Again, we need to be assured that estimated expected values and variances for positive and negative jumps are close to one:

p2 <- sim_p2(t = 1000)

mean(diff(p2$time_p)); var(diff(p2$time_p))

# [1] 1.006591

# [1] 1.054261

mean(diff(p2$time_n)); var(diff(p2$time_n))

# [1] 0.9923275

# [1] 0.8606385

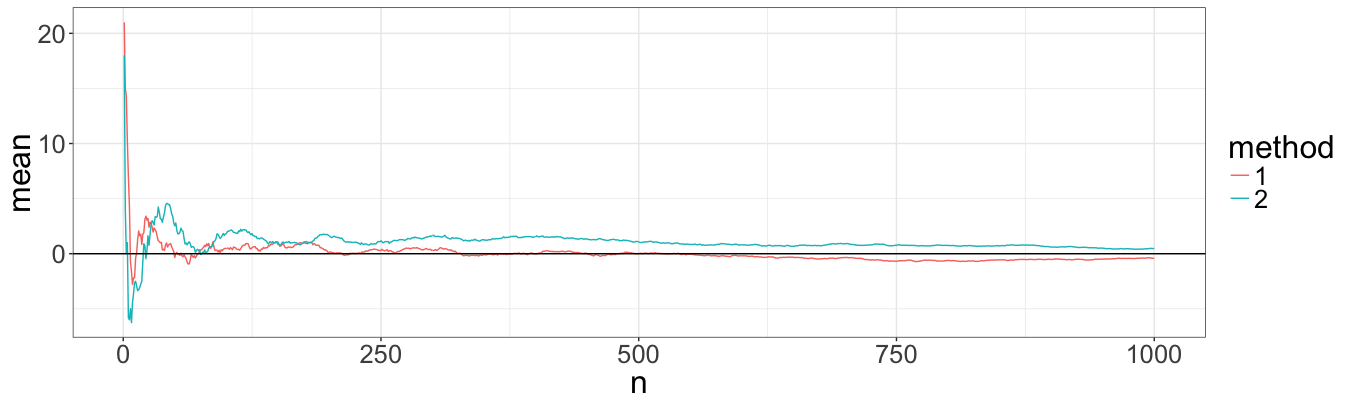

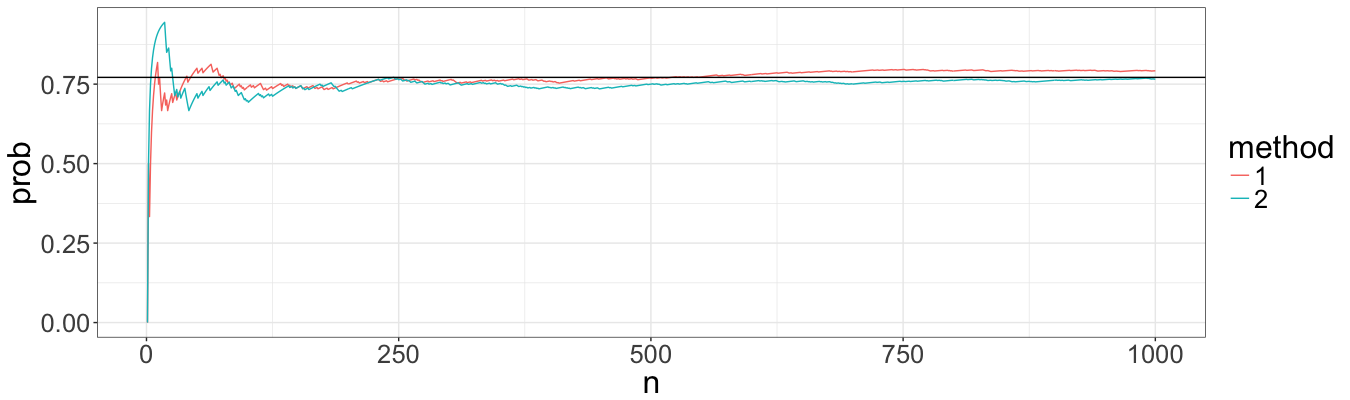

Convergence

Finally, we want visually check if the estimatros are non-biased, and how fast they converge (i.e. which method has a smaller variance). We focus on the expected value of a path, as well as on the probability of the path to be below a certain value. For this we simulate a vast number (1000) of paths using each of methods. Then, we estimae the expected value as a function of the number of simulations by aggregating first x paths.

n <- 1000

paths1 <- replicate(n = n, expr = sim_p1(), simplify = FALSE)

paths2 <- replicate(n = n, expr = sim_p2(), simplify = FALSE)

First, we look at the expected value, which sould be zero given both lambdas equal one:

means1 <- sapply(

1:n,

function(x) {

mean(sapply(paths1[1:x], function(y) y$path[nrow(y$path), 2]))

}

)

means2 <- sapply(

1:n,

function(x) {

mean(sapply(paths2[1:x], function(y) y$path[nrow(y$path), 2]))

}

)

means <- rbind(

data.frame(n = 1:n, mean = means1, method = "1"),

data.frame(n = 1:n, mean = means2, method = "2")

)

ggplot(means) +

geom_line(aes(n, mean, color = method)) +

geom_hline(yintercept = 0) +

theme_bw() +

theme(text = element_text(size = 24))

From the plot it seems that both methods converge with the same speed to the correct value. Huray! How about probabilities?

For probabilites we used a threashold of 10 (arbitrary choosen), and a true value calculated by pskellam package. For default argument t = 10, the distribution of $X(10) \sim Skellam(\lambda_1 \cdot t, \lambda_2 \cdot t)$.

probs1 <- sapply(

1:n,

function(x) {

mean(sapply(paths1[1:x], function(y) y$path[nrow(y$path), 2] <= 10))

}

)

probs2 <- sapply(

1:n,

function(x) {

mean(sapply(paths2[1:x], function(y) y$path[nrow(y$path), 2] <= 10))

}

)

probs <- rbind(

data.frame(n = 1:n, prob = probs1, method = "1"),

data.frame(n = 1:n, prob = probs2, method = "2")

)

ggplot(probs) +

geom_line(aes(n, prob, color = method)) +

geom_hline(yintercept = pskellam(q = 10, lambda1 = 100, lambda2 = 100)) +

theme_bw() +

theme(text = element_text(size = 24))

Again, the probabilites converge to the correct value with approximately the same speed. It means that there are no bias in neither methods, and we can continue extending the function of simulating ruin processes.